“The abandoned motorway ran off into the haze, silver firs growing through its sections. Shivering in the cold air, Talbot looked out over the landscape of broken overpasses and crushed underpasses. The pilot walked down the slope to a rusting grader surrounded by tyres and fuel drums.” JG Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition[1]

“People pigeonhole you as if you are having orgies everyday and eating sheep’s heads and all this kind of stuff. Like some kind of overacted goth deviant. And, yeah, OK, we do all sorts of stuff like that, but… whatever takes your fancy. And on top of that there’s other things going on. The sun is shining and there’s lots to enjoy.” Cosey Fanni Tutti[2]

Harnessing the creative force of urban brutalism and playing freely with taboo themes: subverting popular and political culture, and all the while pushing self-modified synths in strange and violent ways, the pioneers of industrial motored through the musical landscape of the late 1970s with a blank eyed intent. In the popular imagination long associated with nihilistic decadence — sexual adventure, literary subversion and narcotic indulgence — that was only ever a part of the story. Self-deprecating humor, astute social commentary and a willingness to corrupt audience expectations were never far behind.

Indeed, industrial was a music with an iconography and culture all its own and this article will examine its evolution and impact. It’s a big history, so rather than attempting a comprehensive guide, the emphasis will instead focus on originators Throbbing Gristle, power electronics innovators Whitehouse, and multi-media propagandists Cabaret Voltaire. Sitting comfortably?

“Industrial Music for Industrial People” — Throbbing Gristle

“There’s an irony in the word industrial because there’s the music industry. And then there’s the joke we often used to make in interviews about churning out records like motorcars — that sense of industrial… and “industrial” has a very cynical ring to it. It’s not like that kind of romance of “paying your dues, man” of being “on the road” — rock n roll as a career being worthwhile in itself, and all that shit. So it was cynical and ironic and also accurate.”[3]

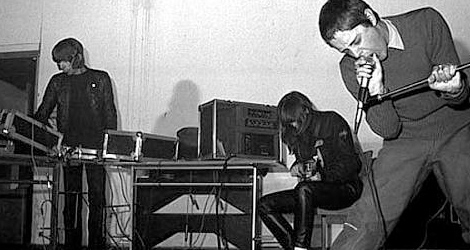

Throbbing Gristle were the originals. They founded Industrial Records and set about making music that brought the shock of the new into sharp focus. Together they evoked an alien and disquieting counter balance to the prevailing musical vista, which punk rock was in the process of revolutionizing. Formed in 1976, the four band members comprised Genesis P-Orridge, artist and founder of the radical COUM Transmissions performance art collective; Chris Carter, mild mannered Abba fanatic and virtuoso synth programmer; Cosey Fanni Tutti, professional artist and stripper who also worked with COUM; and lastly Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson who, by day, worked for a design agency illustrating mainstream album covers.

Throbbing Gristle were as likely to name check William S. Burroughs or Edwardian occultist Aleister Crowley as the Velvet Underground — lines were quickly drawn between music, literature, and art. As industrial was music often occupied with the tactics of subversion, so the visual aesthetic was nearly as significant as the music, grounding the sound to a unique optical identity. Grainy black and white photographs of tower blocks and disused factories therefore took on sinister, behind the corner significance — bleak and disquieting, the dehumanizing aspects of 20th century architecture re-appropriated and given a sickly new half-life. The Industrial Records logo, an innocuous looking chimney stack, turned out to be the incinerator at Auschwitz.

So, bricks and mortar — the physical “industrial” influence — were a vital piece of the puzzle. Chris and Cosey recalled the psychological impact of their rehearsal space, the Death Factory, in a recent BBC interview:

“It was grim, really grim, in a very rundown part of London. The “factory” was an old trouser factory near London Fields and in the basement it was on level with the plague pits, which was why it got called the Death Factory. We were trying to reflect the sounds around us in some weird way. Our studio was in an industrial area and there were lots of different noises going on all the time and we were trying to reflect the way the noises come together in this weird mishmash of electronic experimental textures. We had these home made synths, not Rolands and Korgs — they sounded quite unique, they didn’t sound like regular synths — and then we started building these effects units that you could put guitars or voices through or anything, and we called those Gristelisers. We were never punk — we’re not punk. We’re industrial. An industrial experimental music band’[4]

Debut LP, The Second Annual Report of Throbbing Gristle, was, to put it mildly, a challenging listen. Fragmented vocals, heavily processed synths, “found” sound and abrasive factory noise, unremittingly lo–fi and often submerged in filthy layers of static and hisses were employed to create a nightmarish acoustic effect. Menacing disembodied voices and strange echo effects. Guitars, drums and vocals were put through the Gristelisers — acoustically, it was all there for the tweaking. Made up of a combination of live and studio recordings, the vibe of the record was heavy, curiously devoid of color and imbued with a threatening physicality that hummed with pallid dread. Tracks like “Maggot Death” suggested some affinity with early electronic experiments conducted by Stockhausen or John Cage, but were far more barren affairs:

The subject matter was as bleak as the music. “Zyklon B Zombie” was named after the murderous gas used during the Holocaust. The notorious “Very Friendly” (recorded during 1976 but only released in 2001) recounted the crimes of 1960s English serial killers The Moors Murderers (Myra Hindley and Ian Brady) in excruciatingly matter of fact detail, P-Orridge eking out the syllables in the killers’ names in rhythmic meter by way of chorus, and recounting bland everyday details from court transcripts (“drinking German wine…”).

As such, evil, in TG terms, was not some abstract concept perpetrated by monsters and judged from on high. Rather like a David Lynch movie, it seemed to exist very much in the present — behind the curtains, perpetrated by sentient human beings. Arguably an altogether more disquieting comment than garish tabloid news coverage, they presented dark themes unflinchingly — the full horror — a grey scale subversion of “sexed up” media sensationalism. “Art has to deal with issues of human behavior, and why we behave in ways that are counterproductive, cruel, destructive, aggressive. That’s what I wanted to find out: why? Why are people titillated and stimulated by second hand descriptions of other people’s aberrant behavior? If we can find out what that story is, that has stopped us from evolving with our technology, then maybe we can finally let go of our prehistoric behavior.”[5]

Sensible knitwear and perfect smiles — 20 Jazz Funk Greats

It would be disingenuous to suggest that Throbbing Gristle were all about darkness, however. Third LP, 20 Jazz Funk Greats, was a dynamic and occasionally disarmingly sprightly affair. Largely misunderstood on its initial 1978 release, the record has since become an iconic classic — the closest TG ever got to canonized respectability. Its mischievously ironic title and the cover, which featured all four-band members standing — resplendent in chunky knitware — on a cliff top (which turned out to be English seaside suicide hot spot, Beachey Head) actively goaded any assumption that may have been made about the group. The cover itself was a tongue in cheek answer to a comment made by P-Orridge’s mother, Muriel:

“In passing I mentioned that we were making a new album and she slightly aggressively, and a little sadly asked me, ‘Why can’t you make a nice record for once, and use a nice picture for a change?’ I asked her, ‘Like what, for example?’ ‘Something nice, like flowers,’ she said, ‘and why can’t you smile for a change?’ For some reason, for all the wrong, contrary reasons, this idea stuck in my head. Why not seem to please mum and the general public’s ideas of good taste and pleasantness and yet still, secretly, maintain our perversity?”[6]

Those expecting the brittle assault of Second Annual Report were shocked. Melody, pop, disco, irreverent humor — all were present and correct. Drew Daniel, author of the excellent “33 1/3” guide to the record, recalled his own teenage reaction:

“What I heard sounded to me like pop music. Puzzling and perverted pop, yes, but pop all the same. Given the TG I thought I knew, 20 Jazz Funk Greats was all wrong… what happened to the darkness and evil? This sounded like the work of people who liked to dance, people who listened to disco… people who might be growing up and feeling a bit bored by serial killer trivia’.”[7]

Indeed tracks such as “Hot on the Heels of Love” betrayed Chris Carter’s Abba obsession and synth programming prowess, as well as TG’s mischievous humor. It’s mildly warped but genuinely effective disco track that could almost be taken at face value.

“Wreckers of Civilisation” — Throbbing Gristle Live

It was in the live arena that Throbbing Gristle was at their most visceral. Often eschewing traditional concert venues in favor of unconventional spaces, they attracted infamy after a performance at the COUM organised “Pornography” show at London’s ICA in 1976. The show featured collages of rusted syringes, bloodied hair and tampons while transvestites and prostitutes were hired to intermingle with the public. Conservative MP Nicholas Fairburn publicly — and wonderfully pompously — denounced the group as the “wreckers of civilization” in the House of Commons, helping to galvanize curiosity.

In his sprawling memoir of the early Sheffield industrial scene, Industrial Evolution Mick Fish describes his own shock:

“There was already a palpable violent tension in the air… the whole turgid morass of sound started to pummel the stomach and turn the head into a stodgy muddle. There was something deeply disturbing about the whole event. For me TG had evolved from being a decadent type of art/punk joke into something ugly and tainted.”[8]

Perhaps one of the more bizarre moments in the group’s live history came when they were invited to perform at prestigious English public school Oundle in 1980. The mind fairly boggles at the behind the scenes mechanizations that must have gone into arranging such a show — surely one of the most fascinating juxtapositions in the history of underground music. Chris and Cosey spoke about the gig in a 2011 interview with The Quietus:

“Chris: A whole entourage of industrial people was there, we made it a big event, and they just got carried away with the sound. The kids couldn’t work out whether they liked it or not. They were only kids, I think the oldest was 15 or 16, and you could see the teachers in the balcony frowning and thinking, ‘What’s all this about?’ and then Gen just whipped them into this frenzy, they were shouting at you, ‘Show us your tits.'”

Cosey: I said, no you take your shirt off, and one did, he took his little rugby shirt off and gave it to me. And the pressure I had from Sleazy, he wanted it so bad! When they all broke out into “Jerusalem” we were all [expression of draw-dropping incredulity], it’s as if the instinct kicked in. And in those days! They all started singing. We were all onstage thinking ‘YES!'”[9]

“The Cut Up” — Throbbing Gristle and William S. Burroughs

If the Oundle School show perfectly encapsulated the situationist aesthetic that TG had so expertly cultivated, then the specter of William S. Burroughs represented their most important literary influence — a pivotal part of the industrial story.

Notorious for the publication of Naked Lunch in 1959 — the subject of an obscenity trial — Burroughs (alongside Brion Gysin) pioneered the “cut up,” a literary collage technique involving the splicing and random reassembly of words. As a revolutionary modernist, his work often eschewed anything approaching traditional narrative (although not always — see Junky for a rare example of his linear writing); he extended a vital influence on many aspects of 1960s counter culture. Writing extensively on homosexuality, drugs and the hidden mechanizations of control, he saw humanity — and more importantly language itself — as a living virus. The best of his writing has a lucid quality that presents nightmarish dystopic scenes as grotesque theatrical set pieces. Characters, themes, and even whole passages reappear throughout his books, as does the “Interzone” — a space that bore more than a passing resemblance to the seedier outposts of Tangier, the notorious Moroccan port city in which Burroughs lived and wrote in for much of the 1950s. Throbbing Gristle were big fans.

“When I started to read Burroughs books I just innately started to grasp what he was suggesting: the idea that if you take writing or music and chop it up and reassemble it in a random order you often hear things or understand things that you wouldn’t if you just looked at things in a linear way. And that basic technique of cutting up and reassembling is something I’ve used ever since. I think of Burroughs and Brion Gysin as my two most influential mentors in terms of art and music. Throbbing Gristle was very much set up to incorporate the idea of tape recordings and field recordings and cuts ups — the lessons of the beatniks, and Stockhausen and John Cage — into the music itself.”[10]

The relationship between Burroughs and TG extended beyond mutual appreciation. In 1981, Burroughs released a spoken word LP on Industrial Records, Nothing Here Now But The Recordings. The LP compiled 15 spoken word pieces; each delivered in Burroughs’ laconic Kansas drawl.

The LP was to be the last on Industrial Records for many years. Throbbing Gristle were finished by 1981, a typically terse message informing that “the mission has been terminated.”

The aftermath: Psychic TV, Coil, and Chris & Cosey

Industrial had gained traction as a fully-fledged movement by the early 80s. Bands such as Einstürzende Neubauten in Germany took the “industrial” influence at literal face value, making extraordinary music using home made instruments and liberal quantities of scrap metal, even going so far as to record their first album, Stahlmusic, inside a pillar of West Berlin’s Stadtautobahn Bridge. Around the same time, bands like the Sheffield based Clock DVA were also making waves with a brittle post punk based take on the sound, while SPK followed similarly disturbing ground to early TG, records like Information Overload Unit and Leichenschrie being harsh early examples. The story for the former members of TG was far from over, though.

Psychic TV

Genesis P-Orridge formed Psychic TV, an astonishingly prolific musical collective who collaborated with artists, filmmakers and bands of all persuasions. Musically, Psychic TV generally utilized a cleaner production value than TG, bearing little relation to industrial. They experimented with everything from punk to dance, and jumped headfirst into the nascent rave explosion in late 80s England with a series of raw acid tracks.

Further to this, P-Orridge controversially formed Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth, a loose organisation devoted to making various strands of esoteric philosophy and majick easily accessible to all. But that’s another story.

Coil

Formed by Jhonn Balance in 1982 and joined a year later by “Sleazy” Christopherson, Coil were an enigma among the electronic underground. Hugely influential, their music spanned the gauntlet from abrasive industrial textures to haunting operatic arrangements. Seldom playing live, they instead focused on a rich bounty of studio LPs and released a body of work that was by turns transcendentally beautiful and dread inducingly dark.

Like TG before them, Coil was highly vocal in their interest in both majick and pagan philosophy, with both Christopherson and Balance often discussing occultists Alistair Crowley and Austin Spare during interviews. However, this was no kitsch dalliance. They were highly knowledgeable about the subject — with the library to back it up — and their exploration in the field informed pretty much all of their work. By way of example, first LP How to Destroy Angels was described in the liner notes as “ritual music for the accumulation of male sexual energy.”

Christopherson was a formidable engineer; much of the music he worked on with Coil inhabited a completely idiosyncratic sphere. The world of Coil — and make no mistake, their output exists very much in its own space — is a bountiful place to explore.

“Certain tracks on certain Coil records are designed to trigger altered states, whether this happens or not is to some extent up to the listener. without wishing to sound pompous, we want to make sacred music. I don’t mean something that assumes Messianic proportions or delusions, but I think all good music should be an attempt to change people’s mind-sets.”[11]

An acknowledged influence on Autechre, Surgeon, Aphex Twin and a whole host of other electronic producers, Coil were a seminal band. Sadly, both Balance and Christopherson have now passed on; the former suffering a fatal fall in 2004, the latter a heart attack in 2010. A formidable body of work survives them.

Chris & Cosey/Carter Tutti

Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti have been underground instigators since the early 80s. Exploring synth pop, dark industrial, electro, ambient and all points in between, their output has been as eclectic as it has prolific, spanning some 14 studio LPs as well as numerous other projects.

Early LPs were released on long-standing indie label Rough Trade, primarily exploring a dark synth pastoral sound — “Heartbeat” and “Songs of Love and Lust” are acknowledged classics of the genre. Much of their work is imbued with electric sexual energy. Often eminently danceable — perhaps betraying the pairs knowledge and appreciation of proper disco — Chris and Cosey tracks have also been long highly appreciated amongst the dance community with Carl Craig, Andy Weatherall and Daniel Miller all remixing tracks over the years. On that note, techno enthusiasts should also be sure to check Chris Carter’s excellent but obscure 1981 solo LP, The Space Between. See “ElectroDub 2” for a stunning early evocation of dub techno, predating Basic Channel et al. by over a decade:

“In the studio in Martello Street before TG split up, Chris and Sleazy used to work on their own. I used to come down to the studio sometimes, so we were used to there just being two or three people in the studio working, so it wasn’t a huge leap to be honest. Also because when we did tracks like “Adrenalin” and “Hot on the Heels of Love,” we’d already started enjoying the construction of that kind of music and we wanted to take it a bit further. We’d not exhausted our interest in doing the TG hard-edged stuff but it had become second nature to us and it wasn’t as much of a challenge to us. We were ready to break loose and try something new.”[12]

At the turn of the millennium Chris and Cosey became Carter Tutti. Earlier this year they also released a compelling LP in collaboration with Void (of Factory Floor) under the name Carter Tutti Void. Sexy and driving, the record shows off a new-found brisk functionality, to devastating effect:

Steel City Blues: Cabaret Voltaire

Throbbing Gristle considered Cabaret Voltaire kindred spirits. Indeed, Chris and Cosey released some of their very first singles on Cabaret Voltaire’s DoubleVision label. Formed in the fertile 70s Sheffield scene that also gave birth to the Human League and Heaven 17, they perhaps explored the fractured pop aesthetic more blatantly than any of their industrial peers. Cabaret Voltaire used synths to enhance regular instrumentation but — where Gristle often sounded completely alien in their use of electronics — CV’s sonic markers were more guitar-based.

Formed by Richard H. Kirk, Stephen Mallinder and Chris Watson, Rough Trade put out early singles like the churning “Nag Nag Nag” in 1978 — an (un)comfortable meeting between punk and industrial with guitars, drums and vocals covered in a dense layer of white noise, lending a heavily obfuscated sound to an already busy mix:

However, it was the field of video — particularly homemade edits — which Cabaret Voltaire pioneered. Their shows were notorious for the incorporation of schizoid montages of news sources and cult movies, lending a bewildering and nightmarish intensity to their music.

“Richard was capable of constructing visual backdrops that were like psychedelic flashbacks. The random effect could be like witnessing the whole worlds media flashing before ones’ eyes within a few seconds…. In the same way the Cabs use of snippets of found voices pre dated and predicted sampling, so Richard’s splicing together of visuals predicted much of the pop video making that followed”[13]

During interviews the band were at pains to emphasize the importance of the visual aspect, going so far as to suggest it was of equal importance to the music — another pertinent example of how vital visual identity was to the evolution of industrial.

“I think in peoples senses there is a hierarchy, and the visual side is a lot more spontaneous — people react a lot more immediately to a visual image than to an audio image. Visuals tend to have a greater immediate impact — I’m not saying it’s longer lasting. Audio can be a lot more subconscious, more subliminal, but audio doesn’t have the immediacy of the sense of sight.”[14]

However, if pioneering video experimentation was central to the band’s identity, it was a distinct lack of virtuosity that was central to their acoustic character, something which tied them in neatly with the DIY aesthetic of the punk era. There was a driving functionality to much of Cabaret Voltaire’s best work — put simply, it was raw amphetamine charged dance music.

“We’re very interested in rhythms now. The basic inspiration or philosophy is that we’re primitive, but primitive in an urban way…whether we try to make it commercial or whether we try to make it weird, the whole point is that its instinctive and in that sense I think we’re primitive.”[15] Fish, p.207

“What appealed to us was the idea of providing a faultless beat, a pulse behind what we were doing to link things together. We didn’t really want to use a drummer because we didn’t want to be a part of the ‘rock music’ tradition. In a lot of ways we wanted to parody that whole ‘rock tradition’ and integrate it into the basic idea of sound collage.”[16]

Tracks like 1984’s “Sensoria” were a case in point — poppy but audibly abrasive. Listen to the booming kick drums sitting right up high in the mix:

After 14 studio LPs, CV disbanded in 1996. Kirk had over the years become ever more heavily involved with electronic dance music, recording a staggering number of tracks under an equally staggering number of pseudonyms and working with labels from Soul Jazz and Mute to Warp.

“These days, everyone samples if, say, they want a northern soul feel. In our day, we’d attempt to recreate things. And because we couldn’t really replicate it, what we produced [as Cabaret Voltaire] was interesting and strange. It was the same with Warp. They received demos of what people thought was house music but it was wide of the mark — and as a result, more interesting. Sometimes music works best when you don’t know what you’re doing.”[17]

The oblique pull of “Power Electronics” — Whitehouse

Where Throbbing Gristle flirted with subverting accepted musical territory — disco, pop, synth — and Cabaret Voltaire were yet more upfront in their admiration of pure dance music, Whitehouse were about violent extremity: sonically and thematically they pushed the envelope very hard indeed. Formed in 1980 by William Bennett, they immediately set about testing the limits of electronics to palpable extremes. Bennett coined the term “power electronics” in the sleeve notes to their 1982 album Psychopathia Sexualis to describe what they committed to tape — often monstrous staccato bursts of white noise layered with barked vocals and tempered with absolutely no traditional musical signifiers. Early albums like Total Sex and Right to Kill cemented a place in underground consciousness, while later works grew ever more maximal.

Invoking extreme physical reactions, Whitehouse shows (or, in their vernacular, “live actions,” meticulously numbered and documented like so many military assaults) were highly confrontational affairs in which the band goaded and verbally abused the crowd. This would sometimes boil over to audience violence, with the band dodging projectiles. Whitehouse could push people to the limits of their endurance, forcing them into very difficult and confusing mental spaces.

Philosophically — although sharing surface obsessions — they were a markedly different proposition from earlier industrial bands. Where TG was often at pains to explain the reasoning behind their most controversial works, Whitehouse found this approach anathema, a situation that drew animosity for the band given that they were taken to using graphic — and often sexually violent and fascistic — imagery in their music. Critics in certain quarters pressed that they were duty bound to explain and they were repeatedly accused of glamorizing abhorrent acts and political ideas, taking a sensual pleasure in the macabre, without backing it up with academic rigor.

The leftfield novelist and essayist Stuart Home was a particularly vocal critic of the band, writing at length in his essay, “The Sound of Sadism: Whitehouse and the new British Art.”

“The problem with self-conscious extremism is its need to definite itself against a social norm. In this sense, rather than challenging liberalism, a group such as Whitehouse merely reproduce the reigning ideology… Whitehouse are ‘notorious’ for their track “Right To Kill,” a slogan that takes liberal ideology to a ‘logical’ conclusion. Regardless of whether Whitehouse set out to arrive at a reductio ad absurdum, the notion of rights is very much a product of the enlightenment, and remains so no matter how ridiculous the results when applied to animals and murder.”[18]

However, William Bennett himself strongly refutes the notion that an artist is obliged to rationalize. The following quote comes from a recent interview with The Wire:

“In one sense all art is about some kind of tragedy. I don’t see why some things should be so taboo that they can’t be tackled in some way. We’ve played in Germany and when we get interviewed they always bring up ‘Buchenwald’ and say how can you do that? It’s as if your passing comment in favor of it. But when you think about it there is no content other than the thing itself. In other words what people find so unsettling is the lack of comment.”[19]

The abrasive “wall of sound” aesthetic pushed by Whitehouse was heavily influential on techno — particularly the Downwards/Dynamic Tension Birmingham axis. Anybody who has seen British Murder Boys perform live will pick up a strong Whitehouse accent.

Cut Hands has the solution: an interview with William Bennett (Cut Hands/Whitehouse)

More recently William Bennett in his new Cut Hands guise has signed to Blackest Ever Black, a label with a particularly strong post punk/industrial aesthetic. The tracks he is releasing under the name are markedly different: driving, tribal rhythms that will no doubt excite anyone who was enamored with T++’s Wireless EP of 2010, or any of Regis’ solo material of late. He also finds time to indulge his passion and knowledge of vintage Italo disco in his sets under the name DJ Benetti. I had the following email exchange with Bennett.

What initially drew you to seek out and make extreme sonics?

William Bennett: It’s a long time ago and seen through the mists of time from a now perspective, I’d suggest it came from a combination of a typical teen disenfranchisement: the excitement that comes from embracing something you can call your own and no one else’s. That combined with the emotional rush that this kind of sound had the capacity to elicit, in certain circumstances.

Whitehouse gathered controversy. What drew you to relentlessly explore the darker side of humanity?

It’s the exploration into dark — or unknown — territories where I find the most potential for genuine artistic beauty (and I won’t bore you with my thesis on that): you’ll hear many claims to being adventuresome and edgy and risky and so forth, yet in truth rare are those prepared to confront danger and do something with it, and fewer still resisting the temptation for rationalization. I’m passionate about permissiveness, allowing for the freedom of an unfiltered artistic response.

Does “shocking” mean much to you? Was this ever a creative drive in Whitehouse?

Not beyond what I’ve just pointed out. “Shocking” I see as just an emotional response. As with anything else it’s entirely neutral in and of itself, and is only perceived as good or bad in the light of context; the literalist response to the music always amazed me since there was always a pretty big kind of clue with Whitehouse being the name of the band.[20]

What record are you most proud of from the Whitehouse years?

I don’t really have any favorites, I’m proud of most of them. Racket might be the most intimately poignant.

It must have been intense trying to produce a Whitehouse record. What effect did you tend to have on engineers after weeks in the studio?

Most of the time in studios is spent with people you already know really well which makes things a lot easier. Before I started making electronic music it was much more challenging going into studios and working with people we didn’t know, who were also unfamiliar with our music: I’m sure a lot of people will echo that — just like with sound engineers at live shows.

Could you tell me a little bit about Cut Hands? What provided the impetus to start the project? How did the hook up with Blackest Ever Black come about?

Cut Hands developed fairly organically as soon as the experiments with djembes began — along with learning 15 years or so ago how much our addiction to technology was a major distraction to what I wanted to achieve through music — a Cuban santerÃa priest I knew deserves my thanks for that important lesson. The hook-up with Blackest Ever Black began a while back, we knew a lot of people in common, and the label’s exquisite aesthetic identity was of irresistible appeal.

Footnotes:

[1]J.G Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition, Flamingo, 1993 p.70

[2]Drew Daniel, 20 Jazz Funk Greats, Continuum, 2008, p.23

[3]V.Vale and Andrea Juno (editors), Industrial Culture Handbook, Research, 1983, p.11

[4]BBC Four Documentary, Synth Britannia, originally aired 10/16/2009

[5]Daniel, p. 127

[6]Daniel, p.30

[7]Daniel, p.20

[8]Mick Fish, Industrial Evolution: through the eighties with Cabaret Voltaire, Pop Tomes Publishing, 2002

[8]The Quietus, Chris and Cosey interviewed: from the death factory to the Norfolk fens, Luke Turner, 5/5/11

[9]The Quietus, Chris and Cosey interviewed: from the death factory to the Norfolk fens, Luke Turner, 5/5/11

[10]Genesis P-Orridge, Metalkult Interview part 3: Artistic Influences

[11]The Wire, Coil: Obscure Mechanics, John Everall, issue 134, April 1995

[12]Self Titled Magazine, Chris and Cosey interview, John Doran, April 2012

[13]Fish, p.40

[14]V.Vale and Andrea Juno (editors), Industrial Culture Handbook, Research, 1983, p.45

[15]Fish, p.207

[16]Fish, p.207

[17]The Guardian, Warp Records: Richard H Kirk interview, November 5 2011, David Stubbs

[18]Stuart Home, Whitehouse: the sound of Sadism, http://www.stewarthomesociety.org/white.htm

[19]The Wire, Invisible Jukebox: William Bennett, issue 322, December 2010

[20]Non UK readers should note that “Whitehouse” is the name of both a UK pornographic publication and also the surname of Mary Whitehouse, a notoriously straight-laced 1970s “family values” campaigner.

I’ll tell you what Cabaret Voltaire were like at the Liverpool Royal Court in 1983 on Friday if you like Harry.

Look forward to it Paul

A good article, made unique by the inclusion of the Cut Hands portion and the promotion of Whitehouse to innovators; not long ago they were still derided as ‘too far out’ and not part of the lineage, so it’s curious to see them here. I think this series is great and could be improved by drawing more links between current artists -the aforementioned Blackest Ever Black, Sandwell District, Ekoplekz, White Car etc -and these forefathers. Thanks.

Deguid’s “prehistory”, (still available via hyperreality) still one of Language’s best attempts to assimilate a narrative about musical tradition into aspirations of resistance

[…] “There’s an irony in the word industrial because there’s the music industry. And then there’s the joke we often used to make in interviews about churning out records like motorcars — that sense of industrial… and “industrial†has a very cynical ring to it. It’s not like that kind of romance of “paying your dues, man†of being “on the road†— rock n roll as a career being worthwhile in itself, and all that shit. So it was cynical and ironic and also accurate.â€[3] […]