Listening to Room(s), Machinedrum’s absolutely mind-bending new album forthcoming on Planet Mu, one might think that the man born Travis Stewart is some fresh-faced space traveler repping the hot dance sound of a galaxy far, far away. The latter doesn’t seem so far off — there may not be a single producer on this planet who sounds quite like Machinedrum circa 2011 — but Stewart has in fact been on this planet for quite some time, amassing a genre-defying discography and honing his razor-sharp studio chops over the course of the last decade and change. His latest crop of productions are so hot, we reckon the dance music world will be spending much of the second half of this year sweating them out. Thus, we caught up with Machinedrum in Brooklyn a few weeks before he decamped to Berlin for the summer to better know a veteran we expect is about to get his due in a very big way.

Releasing music on Planet Mu is bound to bring you quite a few new fans, many of whom may think the label just plucked some newcomer. As this is certainly not the case, let’s talk about how you got here. Can you take me back to the beginning of your production career?

Travis Stewart: Well, when I first, I guess, started dabbling in production — before I even really knew what it was — it was probably when I was 12 or 13, and I was messing around with programs like Rebirth, which was a software 303 clone. It had, like, two 303s, a 909, and an 808, and so I was just basically making acid tracks, starting off. And I was using Cakewalk and some other programs like that. But then I really started to dive into electronic music when I discovered Impulse Tracker. It was probably like mid-90s, early-90s, something like that. And the thing that interested me about it was a community that was based around it; there was a whole online tracking community where people would upload their files, which were generally really small because at the time, you know, with dial-up and everything, in order to have a music-based community you had to kind of keep things small. So that actually became kind of a challenge for a lot of people — to see who could make the smallest file size, but best-sounding song.

Smallest file size… like actual audio, or some kind of MIDI-style file?

The actual file size, yeah. Not exactly, like, the length of anything because with the whole tracking scene — or trackers in general — you would save the file, and then it would contain all the samples in it and the sequence. So you could just easily pass it around to other people and then you could see what they did to make the track. So I learned a lot from that. But I guess when my career officially got started, though, was probably around, like, ’98, ’99, when I started sending out demos of my material. I’d send it to Schematic Records out of Miami, and I’d send it to a couple of other labels that don’t really exist right now. And I was sort of doing that and at the same time talking with my friend Gabe Koch from Miami, who eventually started Merck Records. He was telling me, you know, “If nobody really gets back to you on these demos, definitely talk to me. I’m thinking about starting a label with all these people that we know.” He was one of my Internet buddies that I had been talking to when I was living in North Carolina. Because I didn’t really relate to many people growing up, locally, that were into the same kind of music. So I ended up meeting lots of friends on the Internet that were sort of into the same kind of music.

Eventually Gabe decided to release my Syndrone album, Triskaideka, which was, I guess, technically my first electronic project. It’s more, like, IDM Autechre-sounding influenced stuff. So that was my first official release and Merck’s first official release. Then at the same time I was doing the Machinedrum project, which at that time [had a] more drum and bass, jungle influence, or maybe even more of the intelligent drum and bass or, like, I think people were calling it “drill and bass” at the time — like a lot of Aphex Twin, Squarepusher, stuff like that. But I was really interested in the sort of flux between hip-hop tempos and jungle tempos, and how they shared the same tempo, but one was double-time, one was half-time. So a lot of my songs were — the earlier Machinedrum stuff was — more focused on that kind of thing at the start.

So if you were on a very different musical tip from your peers at this point, what were they into, and what were you into?

For the most part, my friends were into rock stuff, and the closest they came to liking electronic music was maybe Daft Punk and Aphex Twin. That was even rare. Or Air, something like that. But most of my friends were into alternative stuff, metal. Maybe a few friends were into industrial, like Skinny Puppy and Front Line Assembly, which I definitely was into at the time. So I definitely found more people who were into the darker kind of stuff, but as far as Warp Records or Skam or any of that underground European electronic label stuff that was coming out in the late-90s, early-2000s — I didn’t really know that many people who were into the stuff.

Maybe it’s a stereotype, but it seems like most teens go through these distinct musical phases, like a classic rock phase or a hip-hop phase. Was electronic music pretty much it for you, though?

Not really. I was into everything, just as I am now. Maybe as I started getting later and later into my high school years I was getting less interested in anything that had vocals. I was mainly into instrumental electronic at that time, but before then I was really into a lot of alternative rock, like Smashing Pumpkins and Hum, and a lot of grunge and stuff like that. But at the same time [I was] listening to, like I said, industrial music and some metal, kind of all over the place.

Eventually you made it down to Florida. Was that the next stop after North Carolina?

Yeah.

And had you released an album at that point?

Yeah, I released my first record [in] the second half of my senior year in high school, in 2000. And then the first Machinedrum release came out in 2001.

You went down to Florida to attend Full Sail, right?

Yeah, exactly, I went for school.

I remember you telling me about a year ago that a big part of why you went there was because you knew that Pharrell [Williams] went there, and that was sort of all you needed to know.

That was part of it, definitely. I was sold on all the good reviews I’d heard — like, people talking about job placement. Just generally the fact that you could have an Associates of Science degree in one year was really interesting to me. I’d tried doing the four-year college thing as a music major for one semester, and after one semester, and just meeting people who were graduating and stuff, I wasn’t really interested in spending four years of my life doing that if I could just have this instant access to a job and a career field that I wanted to do.

Did that experience really broaden your horizons in terms of being a producer? Like, has a lot of what you picked up at Full Sail carried over into what you’re doing now?

I think so, now. At the time I was going to school, I probably would’ve said the complete opposite. [Laughs] Of course, that’s kind of how school goes. But yeah, I think it definitely kind of brought me out of this sort of more — I had a very punk, I-don’t-give-a-fuck kind of mentality before going to school, where all my recordings were blasted out. I didn’t really care about any sort of dynamic mixing or anything like that; [these are the sorts of] tools I kind of picked up in school. So it kind of balanced me out.

It’s interesting what you say about balancing out your production style, because for me, your early Machinedrum albums are all about stylistic navigation. For example, the second album opens up with an ambient tune, and then it sort of transitions into something that feels totally hip-hop.

Are you talking about Urban Biology?

Yeah. At this early point in your career, I sense this tension between this kind of high, electronic feeling and more of a pop feeling. Was there ever a point when you were torn between those two directions, or do you feel like they’re just two sides of your production identity?

Yeah, I guess it’s ever-changing. There’s definitely always been interest in that contrast between both worlds, and [on] some records I focus on it more than others, but it’s sort of just a natural thing that comes out. Because sometimes I’ll be really in the mood to experiment with synths and sound design and stuff like that, and then the next moment I just want to feel a deep groove or something that is really catchy, essentially, you know? And then sometimes both of those worlds come together.

In the last decade or so, you’ve released some singles, some EPs, but it feels like you’ve released at least as many albums, or maybe more. Is there a difference in how you approach putting a single or EP together and how you approach an album, and do you see yourself gravitating more towards the latter process?

Well, I think when I originally started releasing records, it was during this time where I was moreso feeling like I wanted to put as many tracks on a release as possible because that’s kind of what I wanted. Any time an artist would put out an EP or something, I would always want more, and I was like, “I don’t want to do that to my fans.” I would want to give them as much as possible. But I think that’s kind of changed for everybody now. I think EPs seem to be more successful as far as gaining hype and whatnot, and I think it does have to do with the fact that it leaves people wanting more. So you give them another EP, and then that’s more, and you just keep that whole cycle going. So I don’t know if it has to do with people being more ADD than in the past, but — yeah.

My understanding, too, is that you’re able to produce a lot of material pretty quickly.

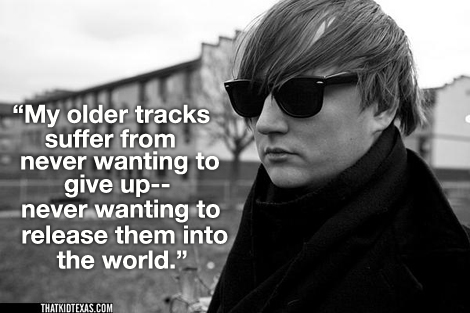

Well, it’s changed over the years because my first few albums — and even Want to 1 2? — I spent anywhere from three months to two, three years on a track, you know? And after just doing that over and over — I don’t know, I kind of got inspired by this one talk I saw. I can’t remember the name of the lady, but it was on TED Talks, and she’s talking about influence and the idea of “genius inspiration,” like, [genius] coming to people in a moment, rather than it being a spread-out thing. It’s like something that you have to grab as quickly as you can, and get down the sketch of it as clearly as you can during that moment of inspiration. Otherwise it gets lost over time. And I think a lot of my older tracks suffer from never wanting to give up on the track, like, never wanting to release it into the world. Like, it’s this precious thing that I could never give up, and now I’ve just — especially in the past year or two — become less attached to the songs, and I try to wrap up as close to the initial conception point as possible, because I feel like the more days and weeks that separate that original inspiration, the more the idea gets lost.

How fully formed is the idea when it sort of first comes to you? Do you hear the whole track in your head, or do you just hear a little clip?

No, not really. I mean, yeah, I’ll hear an idea. Sometimes I don’t even hear anything. I basically just sit down in front of all my stuff and start vibing. Like, I might just start playing keys or go through my sample libraries and find something that’s interesting. And then even that will just kick-start the song, but I might not necessarily use any of those elements later on. But generally during that first session I try to build out what will be the biggest moment in the song. So it’s, like, the most stacked, the most layered part of the song. And once I have that and I can’t really add any other elements, I’m like, “OK, this is ready. I can start arranging this now.” Whereas in the past I would probably start arranging at the same time I was trying to conceive of what the song was going to be. And so over time I would figure out what that biggest moment in the song would be. And now I just try to get that done as soon as possible because otherwise the song’s going to sound, like, too all over the place, you know?

So it’s a matter of crafting the pinnacle moment of the track, and then figuring out how to get to it and how to move past it?

Yeah.

Does that feel like a kind of songwriting? Like, do you think of how you put a track together as songwriting?

Yeah, I mean, everybody has a different definition of songwriting. I mean, some people will technically consider a song, like, verse-chorus-verse, like it has all these rules that [it adheres to], but yeah, I mean, it’s definitely — what I consider my definition of songwriting is the initial conception of a song, whether it’s a beat or even a lyric or even getting down a rough idea of what vocals would sound like over something. Because I still do that — I’ll sing. If I have a vocal idea in my head and I can’t really do anything by chopping up vocals, I’ll just sing it straight into my computer and, like — even if I’m singing gibberish, I try to get out the idea.

It seems like over the course of maybe the last year or year and a half, you’ve started to zero in on bass music. How did you get there?

Well, I mean, the whole concept of bass music has always been funny to me because I think it’s just — it’s an element of a song. I mean, I understand that it is a genre and what kind of subgenres are made out of that. At the same time I just think of it as an evolution in electronic music. Basically what happened, like, IDM — and I hate saying that term — experimental electronica came out of that period in the 90’s where there was a lot of dance music, but people wanted to make it more interesting, basically, and then as it became more and more and more interesting, it essentially became more wanky, and people were just trying to see who could do the most tricks in the least amount of time. And it just became annoying and really unlistenable after a while, especially with a lot of breakcore stuff that was coming out. And I feel like this whole [contemporary] bass music scene is essentially IDM resurfacing in a more dance club context. Like, you have a lot of interesting sounds going on, interesting drum programming, stuff that is kind of off-kilter, but at the same time you have this underlying theme of bass that kind of carries you and just makes you feel good in the club. Because what’s club music without bass, you know what I mean?

I remember reading an interview you did in September of last year, and the interviewer asked you what you’d been listening to recently, and you said you’d been listening to juke and 16th century choral music–

[Laughs]

— and now that I’ve heard your new Planet Mu stuff, which I’m guessing you were working on at the time, these influences totally make sense. Let’s talk about how this Planet Mu material came together. When did it start bubbling up?

I initially started working on all of the material last summer, and probably wrote one of the first tracks while I was on tour in Europe. I was in Berlin, I had a week off, and I started the track “Now U Know Tha Deal 4 Real,” just on headphones. And then I was really happy with the fact that I could come up with a song like that in one session. And I was listening to it over and over, and I was like, “There’s really nothing I want to change with this. This is really just how it should be. I should just strive –” I mean, it sounds ambitious, but it really isn’t. I feel like it’s more ambitious to spend tons and tons of time on a track and try to be super intricate about little details. Whereas this experience and, like, writing that one song in such a quick time, and just being kind of happy with how simple it was, sort of inspired me to continue along that path. So I started writing more and more tracks around that time last summer when I got back to New York. And it would literally be these weekend sessions or just random times where I’d write two or three songs day after day. So I think the proximity effect definitely came into play there: it gave it connectivity, sonically, to all the tracks because there wasn’t as much time separating all of them.

The tracks are fast — we’re talking BPMs from the upper 140s to 160s — and usually fast music can be a bit stressful. But it’s almost like you break the fever in the music, and it just becomes really chill again. I remember you saying earlier that you were into jungle because the tempo could be felt as fast or slow. Did you discover this tempo range at some point during this process of writing these songs and decide that you wanted to focus in on it and exploit its dual nature?

I think, you know, after experimenting with higher, 130-to-140 tempos with the Sepalcure material, it interested me in sort of doing more of that on my own and seeing where that would take me. And where it eventually took me was, I started recognizing this sort of full circle sort of thing that was happening with my music, going back to where I was talking about the hybrid of jungle and hip-hop within the same song. By upping the tempos more and more, I was essentially going back to what I was originally trying to do back in the day when I was starting tracks at 80 to 90 BPM, but, like, going double-time halfway into the song. And so essentially I’m doing that again, but this time with higher tempos, trying to make it feel like a half-tempo. So if it’s 160, there are elements of it that have an 80 feel. And then 150, 75, et cetera.

Photo by Noor One

Hmm… maybe I’m wording this lamely, like I’m asking it on “60 Minutes” or something–

I like the “60 Minutes” comparison.

[Laughs] Yeah. But… speaking to what you said just before about how you’d start tracks “back in the day,” does it feel like with Sacred Frequency and Room(s) that you’re making the music you’ve been heading towards your whole career? Like, has your career to some extent been preparing you to be able to focused on such a specific sound and to be able to produce in the way that you’re now producing this stuff?

I would agree with that, in a way. Definitely. When I moved to New York I was really focused on working with pop artists and trying to bridge everything I’d learned up to that point with a lot of the interests that I had with pop music. And after doing that trial and error, trial and error, after a while I just kind of got tired of really trying to — it’s one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever had. And not that I’ve given up on it, but I kind of had to take a break from trying to bring those worlds together, so I decided to kind of go back to my roots, in a way. That whole time I was learning how to write pop music led into the way that I approach writing experimental electronic. So this [new material] is probably more or less a culmination of everything that I’ve learned.

This is interesting, because so much of the bass music that’s popular in the U.S. right now — the stuff that would be considered “pop dubstep,” perhaps — is really aggressive, really tough. The Planet Mu stuff definitely has a pop element to it, but instead of taking the “brostep” route, you’ve kind of advanced the melodic side of this music. Has the bass music that’s blowing up here in the States now emphasized entirely the wrong side of this music?

I wouldn’t necessarily say there’s any right or wrong approach, it’s just a different kind [of music]. Like, for all the bro-steppers out there, it’s kind of just — it’s a niche that needed to be filled; it’s people that want to go and just scream at shows, and I definitely appreciate that element. For me, when I’m writing songs, I definitely like the element of aggressiveness, because like I said, I come from a background of listening to a lot of industrial music and noise, and I like everything from, like, Wolf Eyes to Merzbow and the Skinny Puppy stuff that I was mentioning earlier. So I definitely enjoy aggression. But I think it’s just natural for me when I’m writing a song to kind of balance it out, because even during the songwriting process I’ll kind of get burnt out on [the aggression], and I don’t want that. I’ll just naturally not want that to happen, you know?

Let’s talk a little about New York. You’ve been here now for —

Five years, as of a few days ago, actually.

Congratulations! So yeah, I actually talked with FaltyDL about this a little bit when I interviewed him recently. New York is this big city, but this little corner of the dance music scene is really, really tight-knit. And there just seems to be kind of a lot of communal energy there. How do you think you’ve been influenced by this place and by this scene?

I’m definitely happy with what’s been going on recently, as far as, you know, the Percussion Lab nights and this feeling of community. Because one problem with New York [and artistic communities here] seems to be there’s a lot of people not necessarily competing, but [the communities are] very insular, and they’re kind of in their own worlds. They’ll acknowledge other people in the scene, but it’s more about them succeeding at what they do. Because this is a very aggressive city; it’s a very high-paced, and it’s expensive. So if you’re a musician full-time, you’ve got to meet that momentum with being very career-focused. So essentially it leads to people not really connecting with others as much as they should and forming communities here. So I’m really happy about the fact that that’s been happening a bit more with the people that are living here.

You’re taking a break from all that this summer to spend time in Europe. Will you be doing a lot of touring there in advance of the album?

Well, at the moment I have a few dates lined up in Europe, got them all on machinedrum.net. But yeah, I’m going to be located in Berlin starting in June until early September. That’s mainly just a way for me to kind of escape the scene that’s sort of young in America [for one that] has already been bubbling for a while in Europe, and a lot of the influences for my newest record are coming from European labels and European artists. So I feel like I need to be over there when the scene’s really going and then come back here when it’s finally starting to get going here.

What are you working on music-wise right now? I’ve heard that that you and Praveen are working on a Sepalcure album right now, yeah?

Yeah, we’re working on an album. We have really been grinding on the album since I’m going to be [away]. So yeah, we’re really excited about that. I’m also trying to tie up loose ends with some different artists I’ve been working with in New York, like Azealia Banks, trying to finish up her EP for XL. And Jesse Boykins III, we’ve had an album that we’ve been working on for a couple of years now that we’re trying to put the final touches on this month. Other than that, I’m still kind of vibing on the similar style to Room(s) . I haven’t necessarily decided to stop making those kind of tracks. I feel like I’m sort of on a momentum right now. Even though the record’s getting put out, I still feel like continuing that same path because it’s really exciting for me.

What artists have you been listening to recently? New stuff, old stuff?

I could break out my iPod right now… I’ve been listening to a lot of old school rave and jungle. I’ve been listening to — what have I been listening to? It’s always a tough question for me. My mind starts racing. I guess a lot of the new Hotflush stuff. This new Back and 4th compilation has a lot of really good stuff on it. The new Lando Kal on Hotflush is really amazing. Really feeling Jacques Greene. Koreless is definitely one to watch. Distal from Atlanta is really, really good. Om Unit, I’m really digging the Phillip D Kick stuff that he’s been doing. It’s really funny, actually, because I made an announcement on Twitter once that was like, “Hey, I’m going to be at this random bar DJing some of these new footwork jungle edits that I’ve made,” and he direct-messaged me a link to a zip of all these new footwork jungle edits that he had just made. So it was really cool to hear that somebody else was on that tip. So definitely check those out.

What else? There’s so much good music, and I feel like we’re really going through a period right now in the past couple of years where there’s just more and more stuff that impresses me, whereas I feel like there was this lull for a while with a lot of electronic music, especially whenever the whole Ed Banger scene was getting super huge. And I didn’t really — not to say that I wasn’t into any of that; I just feel like a lot of the music that came out of that was very shitty, honestly, and kind of boring. And a lot of people were trying too hard to make this, like, aggressive house electro kind of music and just trying to bite Justice and the whole Ed Banger sound too hard. So for awhile there was that, but now I feel like there’s a lot of interesting music that is becoming just really hard to categorize. And that’s really kind of always been a dream of mine — for people to stop labeling music and just start listening and just kind of get into whatever it is without that sort of pigeonholing going on, you know what I mean?

Good interview. Really looking forward to the album. Wasn’t really into his sound at first but the last couple of Machinedrum EPs (in particular the track called “Listen 2 Me”) have completely won me over.

Note – Minor typo in one of the questions here LWE – “Did that experience really broadened your horizons..”

I love the new album….and from that I’ve started checking out his older stuff. I’m impressed!

[…] fantastic record. Right-click for his “TMPL” from XLR8R and check out the interview at Little White Earbuds. The album is available digitally from Planet Mu on July 25th, vinyl/CD to […]

[…] of club genres, using his undeniable pop sensibility as superglue. But sometime late last year, as Stewart recently told LWE, that path came upon a clearing: taken with the notion of “genius inspiration,” Stewart […]