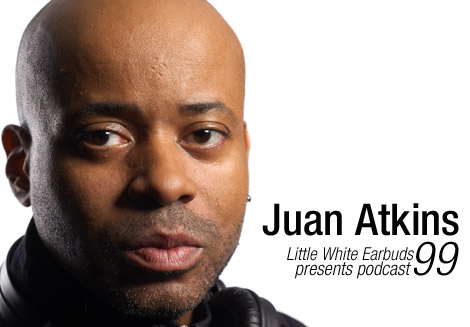

Forming part of the very bedrock of techno, Juan Atkins’ influence on the past thirty years of electronic music is truly immeasurable. His first musical venture, Cybotron, with Rick Davis birthed such classics as “Alleys of your Mind,” “Cosmic Cars” and “Clear,” records which laid the foundations for what would become Detroit techno. On his own as Model 500, Atkins surged forward with his particular vision of electro and techno, releasing further classics in “No UFO’s,” “Night Drive” and “Starlight” among others. Together with Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson the three were responsible not just for a dazzling array of records, labels and aliases, but for creating a movement, a culture, part of music history. There is not much to say that hasn’t already been said about these pioneers of techno, so instead LWE tracked down Atkins to talk about new Model 500 material, some of his early influences and the music that he created that has come to define electronic music. He also provided us with our exclusive 99th podcast, which shows that after thirty years he’s still a vital part of the scene he helped to create.

LWE Podcast 99: Juan Atkins (62:53)

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Tracklist:

01. Wehbba, “The Speech” (Samuel L. Session Remix) [Tronic]

02. Trevor Loveys, “Stay In Love” [Jack Union Records]

03. Lee Burridge, “Here’s Johnny” [Leftroom]

04. Smash TV, “World Wide Wet” [Leena Music]

05. John Selway, “Interplanetary Express” [Tronic]

06. Derek Plaslaiko, “Raw Jam” (Jonas Kopp Remix) [Perc Trax]

07. Room 10, “RM07.1” (Pattrix Phiorio Remix) [Retrometro]

08. Marco Effe, “Zenheiser” [Break New Soil]

09. Carl Craig, “DJ-Kicks (The Track)” [Studio !K7]

10. Shlomi Aber, “Tap Order” [Ovum Recordings]

11. Internullo, “Taifas” (Alex Celler Dub) [Yellow Tail]

12. Shlomi Aber & DJ Sneak, “After Touch” (DJ Sneak Version) [Be As One]

13. Solid Gold Playaz, “Next Faze Of The Game” [Real Estate Records]

14. Skeet, “Come Back Raw” [Monaberry]

A lot, of course, has been written about your legend and the legend of techno, how it came about and everything, but for you personally, can you tell us a little bit about your sort of first brushes with music, perhaps some of the earlier stuff you remember hearing that made you want to be interested in music on a deeper level?

Juan Atkins: Well, I mean I’ve been interested in music probably ever since I’ve been born. I pretty much always knew that I wanted to make music or make a record, you know? I mean even from a very young age. I guess the first time it came very serious [was when] my father bought me an electric guitar for my 10th birthday, and it’s one of those with the built — I think it was a Slingerland — with the built-in amp to amp, and the guitar case was the same thing. You know, the amp was built into the guitar case. So I guess you could say that that would be the defining moment when I was getting serious about a career in music.

So who were the artists for you who made you want to be a guitarist?

Oh man, definitely from my whole music listening career there’s probably been Sly and The Family Stone and P-Funk. Sly and The Family Stone’s “Family Affair” was the first record that I ever bought with money out of my own pocket and going into the store myself. Before that my grandmother used to buy us The Jackson 5 Christmas albums. But I think probably Sly Stone and P-Funk, which [there are] a lot of similarities in those two acts.

I understand that when it came to getting into electronic stuff your first synth was a Korg MS-10. Was there a particular thing about that machine that made you want it? Had you heard it being used in records or anything like that?

No, I actually used to — there was a music store, a piano store called Grinnell’s, which is… actually my grandmother raised me from most of my young, younger pre-school era. And she had a Hammond B-3 organ, and she used to go into Grinnell’s and buy sheet music and get it serviced and everything at the store. And then this store had a back room for all the electronic keyboards, for the synthesizers that were just being introduced to the public at the time. I mean, man, this had to be, like, mid to early 70’s.

Wow.

Yeah. I was, of course, a very young child at the time and she used to take me in there, and I would go back in to the back room and play around, and the synthesizers they had there were a Korg MS-10 and a Minimoog, and these were the first affordable synthesizers that were available to the general public. They were monophonic, you know, nothing fancy, but these were the first small synthesizers that were available to the youth I guess.

And so did you play around on that and it just sounded really cool so you wanted to get that one?

Yeah, we used to go in the store and play, that’s the one they had in the store, so eventually when I was able to get one that was the one I got.

Yeah, cool. So your first documented music was with Rick Davis as Cybotron, but had you been playing in bands before that?

No, that was my first real authentic move, I guess you could say. I mean anything else was just when guys in the neighborhood, we would get together and, during this time, it was playing in the garage in the neighborhood, playing in the garage was a big thing. So we didn’t play, we didn’t have any I guess you could say professional bookings or anything like that or recordings or anything. It was just messing around. So Cybotron was the first real group.

At that point in music, things were definitely band oriented, even if you were making electronic music like Cybotron or Kraftwerk or something. When did you start to realize that things could be entirely self sufficient and perhaps also completely instrumental?

Well, you know actually I started — my first demos were done by myself entirely. So I was always with the concept even though I wasn’t using any drums machines or sequencers, I was using methods that were enabling me to record my own fully, I guess, produced demo. And I would use the record — they had a record at the time called Drum Props, and it was basically just a rhythm track record with just different drum beats on it. Like a live drummer playing out different patterns on this record. It was maybe 10 to 12 different tracks with just drum beats on it. And I would play this record, into — I had two cassette decks and a little mixer, a little PA mixer, and I would play this record through the PA mixer and then record a bass line and drums on one cassette and then bounce it back to the other cassette and keep adding tracks onto it until I had a full track.

Awesome.

So I guess you could say that was my first “one-man band” situation.

Did you see that, at that stage, you know, as a viable sort of thing?

No, actually the reason why I did that [was] because I used to get this magazine called Songwriter Magazine. I don’t know if they’re still around, but they had a contest, every year they had a contest. This magazine would sponsor a contest, and if you won, you won some recording time and a record contract and blah blah blah. So I wanted to enter this contest, but I didn’t have any band members to play with so I had to make my own track to get into this contest. I mean I didn’t win, but at least I was able to enter.

Thatt must have been really strange because nowadays, I know for myself personally and so many other people, have decided to start, you know, on a career in music, they’re influenced by what had come before them, and you’ve cited people like Funkadelic and Giorgio Moroder as helping to influence you. But in terms of actually making electronic music, there must have been very few people at the time where you were growing up who were doing it.

No, nobody in the neighborhood was doing electronic music. I don’t even think anybody owned a synthesizer. At this time, when these synthesizers came out, nobody really knew what to do. You had a couple of people like Rick Davis, who I met in college, that even knew what to do. The only people who had synthesizers, like you say, were Giorgio Moroder, Stevie Wonder, Bernie Worrell from P-Funk and he is who peaked most of my interest in it because of course it was part of P-Funk. But tracks like “Flash Light” and “One Nation Under a Groove” were almost totally electronic, you know?

Yeah, it must be so strange to have not had that help, in a way, of anyone showing you what to do. Nowadays you’ve got, you know, kids can go onto YouTube and see how to play the chords, even. They can see how to program, but I guess it was all complete discovery, wasn’t it?

Yeah, for sure.

And breaking all the rules.

Yep.

I guess from the era, in terms of things being quite band oriented, it seems like you’ve always liked to keep that human element in your music, sort of through vocals, and you can always hear that funk in there.

Uh huh.

Is that important to you to, as far as you can take the machines to always still have a human element in your music?

I don’t think that it is so much as a conscious decision as opposed to, you know, more of a subconscious thing. I mean I think that for me, for making music, I like a lot of my personality to come out in the music, and that’s part of, I guess, the beauty or the fun of actually making tracks or making songs is to see how much of your subconscious thoughts or subconscious creativity can come out in your work. So you know, by me being human, I guess by default there’s going to be a human element to come out in the tracks. But what’s fun is to make these machines, I guess, more organic. But being electronic and still being technologically driven and organic all at the same time, there’s sort of an art to that. Yeah, I think that’s probably what makes Detroit music, myself and Detroit artists stand out. Because a lot of people here, a lot of the other artists, a lot of producers kind of took that as the standard. You know, so when you listen to a lot of next generation techno artists they kind of took cues from what we was doing when me and Kevin [Saunderson] and Derrick [May] and Eddie [Fowlkes] did it. And you know, I think that’s why Detroit still remains popular.

Were you producing first or were you DJing?

It probably all happened at the same time. I mean like I said, my father bought me an electric guitar for my 10th birthday, and I don’t even think mixing records was even conceived at that time. The closest thing that you had to that, I think, during that time was the DJ on the radio that could segue a record into another record. But actually matching beats — actually disco kind of kicked that thing off because of the disco, the four-on-the-floor thing made it very easy to match beats. And I think disco probably created the whole DJ culture.

So when you started doing stuff with Rick, were you playing records?

Yeah, I mean I heard, you know, the disco era came in and a lot of the radio stations changed their format to disco and then they brought — the first DJ that I heard on the radio, his name was Ken Collier, he’s deceased now. But he was on a station called, they called it Disco WDRQ, and he was their house mix DJ, and the first time I heard him blend records — I mean I think he blended something like “One Nation Under a Groove” with “I Just Want To Be” by Cameo, or something. And it was just like, ‘Hey man, I got to learn how to do that.’ But that wasn’t ’til, like, late ’70s, like ’79 or something like that.

Now while you were making music with Rick, were you sort of amassing more and more studio equipment of your own?

Yeah. I mean the first demos — like I said, I was doing these demos, and by this time I was just graduating from high school. And I went to a community college called Washtenaw Community College, and that’s where I met Rick Davis. Now Rick was what you call a quote unquote “electronic musician.” But he was very isolated, I guess you could say. I graduated in 1980 so this was, like, the latter part of 1980 when the funk to disco thing was still kind of huge. So we were still under the concept of, you know, the whole thing was when you were around other musicians [you’d say], ‘Hey let’s get together and have a jam session.’ That’s the only way that you could actually still make music.

A lot of people weren’t aware of trying to do things with drum tracks or doing tracks on their own, other than Rick Davis. So when we met he told me, ‘Yeah, I been doing tracks.’ He was very advanced, way more advanced than I was. He had a DR-55 rhythm composer, which was the first Roland drum machine. Also an MSQ-100 sequencer, it was like an early Roland sequencer. And these things, I didn’t know anything about. I read the back of Giorgio Moroder’s album covers, and I thought that you had to be a computer technician to do this stuff, you know? But Rick really broadened my horizons and introduced me to a lot of the equipment, and he had all of this gear. He had ARP Axxe, ARP Odyssey. He had these sequencers and drum machines, I mean when I walked into his room, he had all this stuff situated in his bedroom, and it was like walking into a spaceship. Because he was keepin’ it dark, he would keep his blinds closed. So all you could see was these LED lights. [laughs] And the way the ARP synthesizers worked, they had lights all the way across — that was the setup on the board. And they had lights just kind of on across this thing so it looked like an airplane cockpit or something. Yeah.

[laughs] Awesome. When you guys kind of parted your ways, you formed Metroplex. Tell us a little bit about that. There can’t have kind of been too many small, independent record labels at this time, especially, you know, dealing in electronic music, or solely electronic music.

No, there was no other labels. And especially in Detroit, that was the only independent label, I mean, you know, Motown was considered an independent label.

But that was also huge.

Yeah. But I mean, yeah, but we used the same distribution. You know, we used independent distributors so you had other independent labels, but they were huge labels, still on independent networks. So I guess you could say this was the first electronic techno label.

So that must have been pretty scary because, I mean, as much of an un-financially viable option as that is today, to start an independent record label, it must have been harder then.

No, it wasn’t scary. Not at all, because basically we just had to have enough money to press the record. I mean it was because the record was popular because [The Electrifying] Mojo played the record, man, and it was an instant hit. So it wasn’t — we didn’t have any doubt about selling records, man, the records stores were beating our door down to get the record.

Oh, okay.

So there wasn’t nothing scary about that.

So was Metroplex kind of influenced from having had a brush with Fantasy Records?

Well, Fantasy, no, what happened was Fantasy picked us up. We started Deep Space Records, which was the label that we started to put out the first record, which was “Alleys of Your Mind” on the A-Side and “Cosmic Raindance” on the B-side. OK, that was the first record, and we came out with our follow-up, which was “Cosmic Cars,” and we used an independent distributor. I forgot the name of the company, but it was run by a guy named Bob Schwartz, and he was also distributing Motown and Fantasy and other independent labels. So he just called up Fantasy and said, ‘Hey man, I’ve got some guys here who are selling records hand over fist. You need to take a look at them.’ And next thing I knew, there was a contract in the mail.

Wow, excellent.

Yeah, so we signed with them.

Okay, so you had a positive experience with them, then.

Yeah, pretty much.

So there wasn’t anything to leave a bad taste in your mouth.

Yeah, no. That was great times. I mean the only… we got caught up in Detroit music politics between stores, like some stores were wondering why they had the record and this store didn’t have the record. And you know, we actually got threatened by rival distributors, like ‘Hey, if you sell to this guy, we’re not going to sell your record.’ You know, that kind of stuff. One distributor was in control of the one radio station and the other distributor was in control of the other radio station. So if you sell to this distributor and the other distributor doesn’t want to stock your record, therefore the radio station they are affiliated with doesn’t want to play your music. So we never was able to really have our music played on all the stations at the same time.

Oh okay. So when did you start playing around with sort of more 4/4 beats, what’s, you know, generally seen as techno now?

Well, I mean, you know, if you listen to the Cybotron album, there was a track on there called “The Line,” which was actually the B-side of “Cosmic Cars,” which was kind of a 4/4 track, 4/4 rhythm. It’s always been kind of — you know I’ve always been interested in that because disco, it was a big influence for me as well. Because it was the late 70’s, man; I was graduating back in ’80, so kind of like my whole high school existence was disco. Well, funk. Mid 70’s disco and funk was kind of intertwined, although disco was a little later. I don’t know if you can remember, a lot of funk groups started doing disco records as well. Yeah, that disco rhythm was always there, but, you know, the funk was there as well.

Yeah, sort of more syncopated.

Yeah.

So did you and Rick play live as Cybotron?

No, we never actually played live together. We did as — there was a festival in Ypsilanti, Michigan called the Ypsilanti Art Fair. And it was sort of the same thing as, just like a festival, but it was in a big open field, and they would do this thing every year at the end of August. And so we got up there and did a little thing. But we was up there with some other musicians so it wasn’t actually Cybotron.

But when did you first do a Model 500 gig?

The first Model 500 gig, I guess you could say, was probably 1995 when I did the 10 year anniversary of Metroplex. And we did a live show in an art gallery, which was in the warehouse district of Detroit, right down east of the Renaissance Center, maybe two or three blocks off the Renaissance. It was Mike Banks, Keith Tucker, and Tommy — I forgot Tommy’s last name. But the other half of Aux 88.

Oh right, Tommy Hamilton.

Yeah.

Okay, cool. Can you tell me a little about the different names you’ve used? Most prolifically, it’s been Model 500 and Infiniti, but some of the other names, your one-off few releases, Triple XXX, Channel One, Frequency. Did these others have a distinct flavor as well, or were they just kind of thrown in?

In a way it was like, when this technology came down it enabled you to do a lot of different things with all these different sounds and stuff. So I thought that, well hey, Cybotron had a distinct sound, Model 500 had its sound, so then also a lot of things that were done for collaborations with other people. Like Channel One was a collaboration with me and a guy named Doug Craig.

One thing I was kind of wondering about, I mean I know you guys all had your own lives and your careers were going in different directions, but it’s always seemed kind of strange, like, you and Kevin and Derrick are always cited as being sort of the birth of, or responsible for techno blowing up like it did, but you guys didn’t really ever collaborate that much did you, actually, on record?

Not really. I mean there were a couple of things, but we never really followed through for all three of us to do it. I mean and the funny thing is that in actuality we did collaborate a lot in the early days. I mean, like, records like “Let’s Go,” everybody was on that record. “Big Fun,” everybody was on that record. But we never really just sat down and credited everybody that was in the session.

Yeah. And I guess you all had your different directions, as well, didn’t you?

Yeah.

So when things really started blowing up and, you know, you all of a sudden get asked to DJ halfway across the world in Europe. Seeing the way that things were there, did that open up new avenues of inspiration for you and your music?

I guess you could say that, yeah, for sure. Nobody really anticipated traveling like that around the world, but definitely seeing different places and going to different cultures and things like that, it influenced you probably more subconsciously than anything. And then the spin that the UK and Germany and other places put when they started producing music and the artists came up, you know, there was a definite different spin put on the music. Like when the people in London kind of took things a different way. You had the jungle element that kind of came in, to me which was a continuation of hip house, which a lot of people kind of forget about. But there were a lot of house artists in Chicago putting hip-hop tracks on their house tracks, which to me was the palette for early jungle music.

Tell me about the first time you heard drum and bass, and how that made you feel, I mean did that sort of open up new areas?

Well, no, to me a lot of people come up with different titles for stuff and different categories for things that they just have to name it something, but to me drum and bass was jungle. I mean the first time I heard the term jungle was — I guess there was a time where Shut Up And Dance was doing — that was what I equated with that next step from hip house to, I guess it was kind of hardcore music, in a way. It was like rave, but then when the Jamaican kind of dub element came into it, it became jungle. And to me, drum and bass was kind of a stripped-down version of jungle.

Yeah. You know, I guess for a lot of Detroit guys, I can’t think of too many other people who have actually embraced that sound. I think from what I can figure, you and, I think, Sean Deason has played around with sort of jungle and drum and bass a bit. Was it seen any differently there? Like, it wasn’t such a good thing?

No, in the U.S. it was something that was kind of unheard of, and there was no audience, really, for it. There was no audience here really even for techno, for our brand of techno, much less the sort of evolution of it. So it was kind of like it was something totally new here. Even just a few years ago I would ride around and listen to this stuff, and people was like, ‘Damn, what is that?’

Wow, yeah. So has there been sort of other moments for you more recently where you’ve sort of re-evaluated music like that again? Like, there’s a lot of bass music coming out of England now has gone from half tempo drum and bass to dubstep, and now it’s gone very experimental. Is that an interesting thing for you?

Yeah, anything new or any evolution in music, especially when it comes to electronic dance music is interesting for me, on one hand. On the other hand, you have good and bad of everything, you know what I’m saying? You’ve got a lot more people dabbling and doing productions and doing music than ever before, I think, in the history of making music. So of course you’re going to have the amateur aspect to things, and just everybody that turns on a drum machine and a sequencer and a synthesizer I guess I should say should not be turning on a drum machine, a sequencer, and a synthesizer. [laughs]

Did it feel back when you guys started travelling more, and I mean this is probably more a question for Derrick because he was sort of a victim of it more, but when some of these English groups started sampling you guys early on and that started blowing up, I mean did you guys take offense to that?

No, I mean it was kind of flattering in a way to hear your stuff come back, that somebody would take the time to take your music and use it on one hand. But then on the other hand, the next reaction was, like, ‘Well, damn, am I going to get paid? That’s my music.’ [laughs] So it was kind of a bittersweet thing.

Yeah, yeah. What was it like working with the German guys like Thomas Fehlmann and Moritz von Oswald? Did they have a really different approach to music?

It wasn’t really that different. The thing about that was that they were really — this was at the time when a lot of digital, the really digital thing kind of came and swept in. You had sort of a backlash in a way where you had a lot of people that wanted to still use analog gear or prided themselves on digging up these old analog synthesizers and gear. And they were big on that. So as a matter of fact, like Moritz, his studio, Love Park Studio, was the first time when I’d seen an 808 and a 909 with MIDI on it, and so they had this interface, a box that turned control and CB gate and gate voltage into MIDI. So it was nice to work with them and the fact that you could MIDI up all these different old keyboards like Prophets and Junos and stuff like that.

And your personal studio, has that kind of always evolved with the times, in terms of what technology offers?

Pretty much, yeah.

So when did you sort of start using computers for sequencing?

We had one of the first systems, one of the first software-based sequencers was called Dr. T, which was run on a Commodore 64. I mean it had its glitches. It definitely had its bugs in it, and as a matter of fact, I went back to sort of a hardware sequencer because of all of the hiccups that software had. I mean of course they’ve ironed it out now, but that early stuff had a lot of hiccups in it. But the concept was good, though, because it had a lot of power. Because if you use the computer, of course you had unlimited memory, basically. And so it was a different thing to be able to use the computer with your sequencing. It was like, ‘Aw, man, we’ve got thousands of notes that you can record.’ This was at the time when we were first recording that there’s notes because each note took up so much memory. So the thing was, the selling point was that you can record 1,000 notes. A 1,000-note recording capability, this was the selling point of the early software stuff.

I know throughout your music, science fiction and the concept of space, things like that have been recurring themes in your music. What sort of other ideas have you liked to reflect on?

Nothing else, actually that I guess peaks my interest. Other than just thinking forward and moving forward.

I mean have there been incredible books that you’ve read, you know, that you’ve sort of thought about and made music because you’ve read them?

Not really. I mean, I’m kind of a spiritual person. There’s one book I read called The Game of Life and How to Play It. I forgot who the author was, but it’s sort of a spiritual sort of self-help thing. You know, it talks about thinking positive and being positive, and you know, you have to see yourself in positive situations before they can actually happen sometimes, you know?

Yeah, I remember hearing “Ocean to Ocean” for the first time and really figuring that must be quite a driving force for you.

Yeah.

Are there any aspects of your career that you perhaps don’t enjoy so much now as you used to?

Well, the major record companies have always presented a sort of a crazy approach to stuff. Because sometimes I think a major company, major companies are kind of too big for their own good, and they kind of lose touch with what is really out here or what really the people want. Commercialization comes in and radio controls it, and advertisers control radio, and it’s just a vicious cycle. So that has always created sort of a, I guess a dynamic to getting music to the people that want your music. Because I mean major companies, like, the whole CD thing — record companies are always promoting a progressing thing to of course help the major companies, and the CD kind of killed vinyl, but the independent companies and small labels thrived on vinyl. But it kind of upset the major marketing vehicle because the records– I’ll give you an example: Our record “Cosmic Cars,” when we came out with “Cosmic Cars,” we came out right out at the same time as Prince’s “Little Red Corvette” came out. And in the Detroit charts, there was a radio station that kind of had a chart, and it kind of controlled what Detroit was representing. Like, each city had a major station that had a chart. “Cosmic Cars” was number one on this chart. “Little Red Corvette” was number two. And, man, the record companies and the promoters went crazy because they were like, ‘Who is this? Who are these guys? Who is this Cybotron? We got millions of dollars of promotion behind this Prince, and these guys are beating us out in the charts.’ [laughs]

That’s crazy.

Yeah. So you know, when they came with the CD, that format kind of scrolled out the independent things so things like that didn’t happen. So we figured out how to make it cost effective to start making CDs. And then I guess it kind of changed, but there was a moment when the CDs kind of scrolled out all the independents. A lot of distributors, a lot of vinyl distributors, that was the reason that a lot of them folded, because the major companies killed it with the CD format.

I guess especially when you’re dealing with a format that’s good for DJs, CDs are just aimed at being albums.

Yeah.

So tell me about Model 500 now. When did you decide to re-form in the current line-up?

Well, you know, most of all the Model 500 recordings are me. I did [them] mostly as all just me, Juan Atkins. No collaborations with anybody, and when it came time to play live, I wanted to create a group. I wanted a band, I just always wanted the entity. That’s why I didn’t just go out as Juan Atkins, I called it Model 500. Because that was just something that, because Submerge, which is Mike Banks’ distribution company, was distributing a lot of Metroplex stuff, he would come to me and say, ‘Hey, man, I’ve got a lot of inquiries about a Model 500 show. Why don’t we get together and do it?’ And I said, ‘OK.’ So we just got together, me and him, and we recruited a couple other other guys, Mark Taylor and Milton Baldwin, and just hit it.

Cool. And so you guys recently released a new single, or earlier in the year. Was that a complete collaboration between everybody?

That was a collaboration. That was the first Model 500 collaboration. That was me, Mark, and Mike Banks. Yeah, “OFI,” “Object Flying Identified.”

And can we expect more?

Oh yeah. Well, I don’t know if it’s collaborative. There’s a new Model 500 that I’m just finishing up, the main track on this EP is called “Control.” And from all indications of early feedback that I’m getting, people are loving this track. So it’s like an electro track, something with my new kind of thoughts and ideas, my new sound on it. So it should be coming before the end of the year.

Excellent. Is that going to be on R&S as well?

I think so, yeah.

Do you still release on Metroplex?

Yeah, we may even release — this next single may have a joint Metroplex/R&S release.

Great, well thank you so much for talking to us and thanks for all the years of music.

Thank you.

The version I got through iTunes ends with three minutes of silence, which arrives rather abruptly. Is it supposed to end that way, or did something go wrong somewhere? But very nice . . .

@ Dan, that’s how we received it. Think of it as a sudden call for reflection.

Aha! Also, this is a fantastic interview – I feel bad for not saying that in my first comment.

Juan is the master. Thanks for this. Refreshing mix, not trying to be trendy, just funky electronic grooves.

Great music. However, Audacity shows that a lot of the recording is distorted. I prefer carefully recorded mixes, as they sound better.

Given that both of your last comments were about podcasts sounding distorted, maybe you have your volume too loud…

I swear this had Layo and Bushwacka the longest day at the beginning of the mix a couple of days ago and now it has gone, how is this possible ???

GREAT SET N GREAT MiX…. Very Good

Holy track wreck at 37!

[…] programme : une heure de mix mais aussi une interview où il parle de sa première guitare électrique, cadeau reçu pour ses 10 ans et  raconte […]

[…] Little White Earbuds podcast, this one is courtesy of a true pioneer: Juan […]

[…] Juan Atkins @ LWE Podcast 099 […]

[…] 99th podcast was put together by the godfather of Detroit techno, Juan Atkins. Be sure to add it to your collection before it’s archived this Friday, September 7th. » Eradj Yakubov | September 2nd, 2012 […]